Con Edison Immigrant Artist Program Newsletter, Issue No. 31

Featured Artist: Hector Canonge

Hector Canonge is an artist who has engaged in multiple disciplines over the span of his artistic and activist career in New York City. He studied Comparative Literature, Filmmaking and Integrated Media Arts and has participated in various artist residencies throughout the city. His work uses a broad range of media which include the use of commercial technologies, physical environments, and cinematic and performative narratives.

Canonge actively engages in exploring contemporary issues that impact immigrants in New York City. In many of his performance and public works such as Tabula Lunar and Scar, he makes use of technology to enhance audience participation and bring the message home for the viewer. Canonge is a leader in various initiatives that foster the collaboration of artists in the culturally diverse borough of Queens. His initiatives include CINEMAROSA, a film series that fosters the integration of LGBT communities in Queens through the creation of cultural film media programs; QMAD, a non-profit cultural organization that produces and implements programs in the arts and communications media to encourage Queens’ multicultural communities to come together and forge an artistic identity for the Borough; andA-Lab Forum, a monthly forum that brings in artists at various art spaces in New York City. Canonge’s work has been reviewed by The New York Times, ART FORUM, Hispanic Magazine, and The Queens Chronicle, among others. His projects have been followed by media like NY1, NPR Radio, UNIVISION, and CNN.

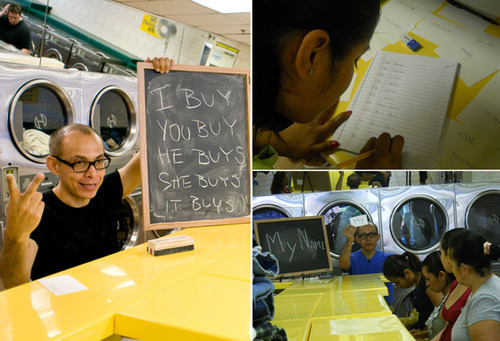

Most recently, Canonge completed a residency with The Laundromat Project: Create Change Residency Program in which he developed his project The Inwood Laundromat Language Institute which is a school for teaching English and a platform for collecting stories about the experiences of learning a new language for immigrants. NYFA’s IAP Program Officer Karen Demavivas and Intern Dennis Han interviewed Canonge about his experiences, his thoughts, and initiatives involving immigrant issues and collaboration in New York City.

IAP: Your projects explore a diverse range of topics from issues like AIDS to how various cultural influences affect the human psyche. Do you find yourself converging on one or more particular paths or do you seek to branch out more?

HC: For me art is an experience that I breathe and live. I couldn’t say that I’m branching out to any particular practice. As I evolve and grow as an individual and as an artist, I find new modes of expression that I am not afraid to explore and experiment with. The topics I’ve been able to explore are diverse and encompass various forms of media production from using mobile networks in the creation of collective narratives in “Ciudad Transmobil,” to adopting commercial barcode technology to tell stories about HIV/AIDS in “200mm3,” or to mapping terrains with satellites and geological data interpretation in “Parallel Grounds.” From working with environmental issues related to the production of crops and Genetically Modified Organisms, GMO’s, in “Deceptive Landscapes,” to spending thirty hours inside a luminescent cage in the gallery writing stories about immigration with “Golden Cage,” are examples of the things that I’m concerned about. No matter what tool or technique I adopt, my intellectual and formative background also comes afloat. I studied comparative literature so narratives are very important in my projects. I have a filmmaking background so cinema is very present in my work, and the same can be said for my Integrated Media Arts practice where technology is present but very much as a tool or mechanism.

IAP: In some of your interactive works such as Tabula Lunar, Scar, and Schema CorpoReal,audience participation through technological means was key to the experience. Can you explain why this interaction was important to the experience of these works?

HC: In my projects, installations, and performance art work interactivity is an important component. I believe that by having the public directly involved with the artwork, they are closer to my meaning and concept. I come from a film background, where an audience is pretty much a passive recipient of the visual message, so when I started working in Integrated Media Arts, I realized that I wanted a more direct participation of people. In Tabula Lunar, for example, passers by become part of the projected images as they get placed on its lunar surface. It was fascinating to see grownups and kids trying to jump like the astronauts on the moon. They became part of the visual narrative monumentally projected above them out on the facade of Coliseum Theater on 181st Street and Broadway.

With Scar, I appropriated the dynamics and narrative of a shooting game, and using an X-Box, I prompted people to pick up a toy gun and shoot at criminals extracted from the film Scarface. At the beginning people were a little cautious or self conscious about picking up the gun, aiming at a target and shooting through this cracked mirror, but once they got do it, they couldn’t wait for their turn to have the shooting experience. Scar reflects on the glamorization of violence, the attitudes of heroism and how fictive narratives become translated to real life popular urban culture.

In terms of my performance art work, I also engage with the public. For Your Blue Eyes Melt My Bronze Soul / Tus ojos claros derriten mi espíritu de bronze, a piece about colonization and control, I gave people little bags with red paint that they put on their palms so they could slap or touch me leaving their palm imprints on my body. I was slapped many times and touched in various ways, but what was interesting was how people engaged and wanted to take part in the experience. For GRANADA, a performance work about war in the Middle East, I popped pomegranate arils in people’s mouth, and then ate the dry seed. They couldn’t wait to have the drops of the red juice in their mouths. I was moved and thrilled by people’s active reaction to my work, even more so than when they passively watched my earlier films.

IAP: You hold a compelling take on certain aspects of society often through the lens of technology. How have you engaged with immigrants as well as non-immigrants and the establishment through this lens in relation to the politics of migration? What are some good practices of dialogue that you can share?

HC: In many of my projects, technology is the means and not the end of what I conceptualize and create. Working in New-media has allowed me to explore the different connections that I can make with the public. My New-media Art work is accessible and non-intimidating. For example, with my project IDOLatries, I used the barcode labels on Hispanic food products in order to trigger visual narratives about feminine archetypes. Then the project was exhibited, it was fantastic to see people’s reactions because they are familiar with the bottles, packages or cans. I think the project would certainly have a different resonance if it were to be presented in Norway or Japan because of the cultural and traditional distance to the particular objects. In the same manner, the project INTERSECTIONS uses similar technology, but this time used as a mapping system for food vending trucks in Upper Manhattan. The location of the trucks and their plate number is codified in the barcode, and people can see them on the map, scan them and trigger the video interviews.

While doing some of my projects, particularly those dealing with immigration issues, I’ve been able to work with various local groups and with politicians who support my vision. It is important for me to establish these types of alliances because my work is not created in a vacuum, and I wouldn’t like to have them stay there.

My recommendation for this type of work is to know what your goals are, and to determine how that relationship will move the art project forward or will maintain its presence and relevance for the future. My grandmother used to say “Lo cordial no quita lo valiente” (Being cordial does not strip out one’s courage) so I approach all aspects of my work, including the not so fruitful ones in that fashion. I know what I want, and I can tell you so in a respectful but matter of fact type of way.

IAP: Over the years, how have people changed or evolved in their response to your works and the message they communicate?

HC: I was welcomed into the art world with a certain degree of skepticism, but also much wonder and interest. When I first presented my mobile-networked project, Ciudad Transmobil, at the Queens International Biennial in 2004, the museum was interested in my New-media installation, but technologically it represented a challenge. The curator was supportive, but I don’t think she fully grasped the new concept. So when she realized that I needed computers with faster processors, flat screen monitors, high speed Internet connection, and a load of materials to transform the gallery space, they pulled me aside, and after long talks, we were able to negotiate without compromising my vision. That was my first experience working with art installers, technicians and a whole team of people who were very supportive. I must say that I turned the museum upside down, but I guess that was the whole experience. Since then, I’ve been more careful and extremely clear with what is needed to carry out, install, or create my projects. I make sure curators, gallerists, and art administrators fully understand what I want to achieve.

Over the years, I’ve worked with incredible people who have been very supportive of my work. Though I have a clear idea of what I want to achieve with every project, I am open to suggestions and possible alternatives for their implementation. I listen to curators, consider the options, and ultimately decide. In that sense, I’m easy to work with, but I am also very demanding because I know what my vision is. Just as some curators love and understand my work and multidisciplinary approach, there are others who want to box or label me into what they are traditionally accustomed to work with; painters, sculptors, photographers, video artists, etc. I don’t fit in any of those categories so they exclude my work or don’t take the extra steps to learn more about my approach of integrating technologies, art, and community engagement. I don’t follow curatorial trends so I’m this rare hybrid who is always transforming and evolving right in front of their eyes. For many curators it’s probably challenging and disquieting.

The public finds my work accessible and they understand what I am trying to communicate. It may take them a few minutes to realize how they must interact with a piece, but once they do, they certainly don’t need me to be next to them to translate its meaning and content.

IAP: You have been involved in various residencies over the span of your career. Your latest one was with The Laundromat Project: Create Change Residency Program in 2011, for which you developed your latest project: The Inwood Laundromat Language Institute. How have such residencies helped you in developing ways to serve the immigrant community through self-expression and learning?

HC: Some of my projects have been developed as part or as a result of having been involved in residencies, fellowships, art commissions, and/or exhibition invitations. For example, with my project Dystopic Walls, a commission by Queens Museum of Art for the program Corona Plaza, back in 2007, I intervened a Western Union store transforming its long hallway with a zig-zag wall that represented the wall being built along the US – Mexican border. The installation had two sides, one that represented the US with its polished black surface, and the other, representing Mexico, and by extension Latin America, had a rustic, unfinished appearance. People, entering the Western Union branch (located outside Corona Plaza on 103rd Street and Roosevelt), encountered this massive structure, and if they paid close attention, discovered peepholes through which they could see digital images of Latin American cities representing the immigrant communities established in Queens. In the same manner, as people exited the business, they could see through peep holes of the US side, digital slides of cities in the US that are densely populated by immigrants. The experience of working in a public environment such as the one encountered at a Western Union branch, gave me a better understanding of immigrants’ connection with their homeland, their family’s survival, and the interesting dynamics of economic dependency. The project also included a series of workshops for children and their families. While children created flags that identified their ethnic origins, parents wrote letters to their loved ones, that were sent to them using Western Union.

With Intersections a project that integrates New-media mapping technology, and organic elements, I worked with immigrants living in Washington Heights and Inwood in Northern Manhattan. Through a grant from LMCC Manhattan Community Arts Fund (MCAF), the project took place in 2009, and it allowed me to learn about food culture and the appropriation of public spheres, like sidewalks and street corners, by food vending trucks and their clients. The bright, colorful, and unique food shops called my attention one day as I was passing through Amsterdam Avenue and 177th Street. The neon signs, many times not fully working, were beacons of changes in the attitudes and practices of immigrant residents in the urban terrain. I spent a few months, visiting the various spots where immigrants congregated late at night. Patiently, I developed a relationship with the food vendors, and learned about their work and lives. For example, I found that many of them were not the owners but employees working long hours as undocumented migrants. Many vendors wanted to participate in the project but when I was about to interview them, they decided not to take part. The few who did risked loosing their jobs, or being deported. At the end of the project, the fascination with the colorful trucks became faded and suddenly they were not as bright as I once thought.

Following these two projects is a series of works exploring immigrant lives, where traditions and experiences are the focus: From mapping immigrant communities along the #7 Train in Queens with the project 18 BEATS, to setting up talks in hair salons or barber shops in Northern Manhattan, HAIRTALK, to publicly performing in Jackson Heights TRACE-ABLE, and to setting up a month long English school with the “Inwood Laundromat Language Institute” in Northern Manhattan. Through these works I’ve not only been able to address issues imbedded in the immigrant experience, but I’ve also learned to recognize the various factors that make every experience so unique yet similar when it comes to ideas for a better future, homeland, and family.

It is very important for me to work from inside the communities I explore rather than assuming an anthropological approach. With my latest public art project, The Inwood Laundromat Language Institute (TILLI), I spent a month teaching English courses to Hispanic immigrants inside the local laundromat, Magic Touch. The project was in a way the continuation of my exploration of the notion of “school as art or art as school” that I had started with AKA, Active Knowledge Academy, in the Bronx, and with the performance-lectures, Immigrant 101, first presented at Panoply Performance Laboratory in Brooklyn.

For TILLI, I set up a whole systematic and aesthetic approach for an institute. First, students received all the materials (notebooks, index cards, pens, pencils, erasers, and even card holders) bearing the logo and the colors of the institute. Second, participants were asked to commit themselves to attend the classes twice a week, either in the morning or evening schedules, for a whole month. Third, the whole learning experience was to be based on what was available in any laundromat: soap, clothes, equipment, etc., and then learning basic English conversation. And fourth, the project was documented and archived. The result of the courses culminated in a public reading of students’ compositions in English. It was an incredible experience to see people transform themselves as they learn basic English. I developed a relationship with participants. Classes became more than just classes. The laundromat was no longer a place for dirty clothes, but a school with portable blackboard and students who did not mind to stand up for more than an hour bearing the Summer heat, the fumes coming from the dryers or the noise of the washing machines. When classes were taking place, the Laundromat was the school, everything else seemed to adapt to our presence. Everything became the art project.

IAP: As an immigrant artist who is passionate about fostering collaboration among other immigrant artists, you have established initiatives such as QMAD, A-Lab Forum, and CINEMAROSA to support this community. What are some of your insights in facilitating the collaboration of these artists in order to build solidarity amidst such creativity?

HC: The acronym that I use on the back of my business card reads: CONeKTOR, is a take on my own name without the H, and with the Spanish word “con” for with, so it phonetically reads “with Hector.” So it’s the idea of connecting with me and, and I being or serving as connector with and among others.

I foster collaboration with other artists because I believe in the importance of dialogue, exchange, and relations. It doesn’t matter where my artist friends and colleagues come from, they could be from China, Mexico, Oklahoma or the Bronx. The fact that my work and initiatives have involved other artists who had been born abroad or beyond state lines has not been purposely proposed. If I find in them a good rapport, common interests, and challenging conversations they have my attention and respect.

CINEMAROSA, the monthly Queer film series that I launched in 2004, was to connect with the LGBT community of Queens by way of screening gay, lesbian, and transgender films from local, national and international artists. I make it a point to have the filmmakers or people involved in the films share their experiences and stories with the public. QMAD, Queens Media Arts Development, followed this first initiative, as its co-founder and current director, I’ve had the opportunity to work with people that believe art -exhibitions, film screenings, and media programs- should be brought to the people rather than expecting people to fill out a gallery space or screening room. Through QMAD, I was able to do more since it is incorporated as a non-profit cultural arts organization. Presently it serves as an umbrella for a number of other programs such as FRAMING AIDS, the annual project to raise awareness about HIV/AIDS in Queens; A-Lab Forum, the monthly artists’ presentations; Space 37, the pop-up gallery in Jackson Heights, and the newest project, ITINERANT, a seasonal performance art festival in Queens.

I spent many hours working alone with my own projects in the studio or involved with programs and projects related to QMAD. As much as I enjoy this solitary process, I am also very sociable and like the company of people particularly if it involves other artists with whom I can talk and relate. I create opportunities for engagement because I know that, just like me, there are other artists who want to connect, contact, and belong to a group or be involved with audiences outside the four walls or their homes or studio space.