A Conversation with Fiscally Sponsored Artist Natalie Bookchin

“I see my role as a filmmaker as that of a careful listener, and my editing performs a kind of close, subjective listening and distillation of the large body of narrations I collected.”

Artist Natalie Bookchin recently returned to the East Coast where she continues to explore sociopolitical themes and shifting narratives in her studio practice. Natalie navigates the terrain of constantly evolving media to engage with contemporary social issues. She generously shares her time and insights with NYFA Current as she discusses her fiscally sponsored project Long Story Short.

NYFA: Congratulations on your recent acceptance to NYFA Fiscal Sponsorship with your project Long Story Short! Why did you choose to apply for sponsorship?

NB: Thanks! I moved back to New York in the summer of 2014 after being away for 18 years. NYFA seemed like the right fit as fiscal sponsor as I began applying for finishing funds to complete Long Story Short.

NYFA: Long Story Short is an experimental documentary film addressing poverty in America. By utilizing interviews and video self portraits from low-income individuals, voices from within this community compose the narrative. How did you choose a documentary film to share this story? How did the project evolve between its conception and final output?

NB: I began the project by building an archive of videos of people narrating their views and experiences of poverty. I wanted to focus on the voices and views of many rather than on a select few. Given the large number of people in poverty in the US, there is shockingly little representation in the media, and the representations that do exist are often deeply flawed. Conventional documentaries typically focus on one or a few charismatic individuals who often stand in for whole populations and frequently, against all odds, rise up out of humble circumstances. Many of these uplifting stories are just that, fictions, and tend to avoid the much darker truth that in America, despite resilience and good character, most people have very little chance of moving outside of the class in which they were born.

I had first envisioned Long Story Short as unfolding in three platforms – online in interactive form, as a film made for the screen, and as a multi-channel installation – but after gathering and working with the material – hundreds of hour-long interviews – I realized that the best way to represent the overall sensibility, tone, and content of the archive was to make a film.

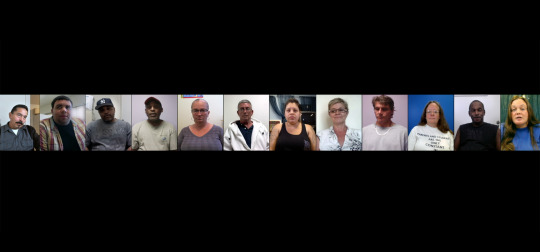

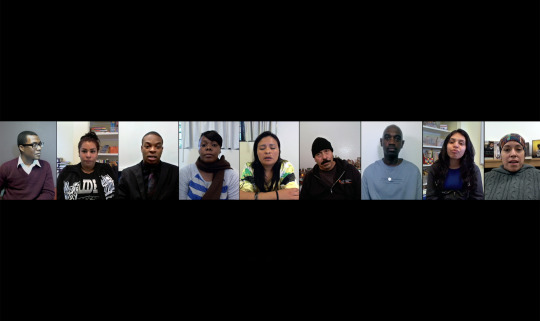

I developed a structure in the film that moves between choruses of speakers and soloists, between instances of sameness and difference and allows the voices of many shared and divergent responses and reflections on poverty to be heard. Composite sentences and conversations unfold across a body of speakers across the screen, as if across a social body, producing a collective of shared ideas and overlapping words, experiences, and phrases spoken simultaneously with variations by multiple speakers – like jazz or an improvised musical score. A tension is produced between isolated individuals – in their individual frames and within the trauma of poverty – and the potential power and solidarity of the collective voice.

NYFA: What logistical or creative measures do you utilize to ensure the voice of participants is paramount in Long Story Short? Is the editing and distribution of the process also collaborative? How does this work?

NB: I see my role as a filmmaker as that of a careful listener, and my editing performs a kind of close, subjective listening and distillation of the large body of narrations I collected.

All those who made videos receive credit in the film, and will be invited to attend screenings and to participate in Q&As. I am in touch with some of my subjects through Facebook. With the instability in the lives of many that I interviewed, unfortunately some participants will probably not be reachable by phone or email. I plan to returning to the organizations where I conducted the interviews – the homeless shelters, food banks, job training programs, and adult education centers – to present and share the finished film.

NYFA: How does your background in art influence your work as a filmmaker? How did you start working with the moving image and what connections do you discover working between different mediums?

NB: I would define myself as an artist, rather than a filmmaker, albeit one who has been working with moving images since the very beginning of my career. My work has long been concerned with creating works that produce shifting subject positions within socially and politically charged and reverberant narratives. Early on, in works like The Intruder, from 1999, I was interested in shifting viewer identifications within a narrative. The Intruder was based on a particularly brutal story by Jorge Luis Borges about two brothers who live in the countryside outside Buenos Aires at the turn of the last century who fall in love with the same women. Her presence so disrupts the brother’s close relationship that they decide to get rid of her, first by sending her off to a house of prostitution, and then by killing her. I saw Borges’ parody of the excessive machismo of Argentina at the turn of the 19th century as a mirror for computer and gaming culture at the turn of the 20th century, where there was also little place for women. In my retelling, the story unfolds by playing a series of 10 online games, each based on classic computer arcade games, such as pong and space invaders, that also incorporate elements of the story within its mise en scène. Players advance by enacting violent metaphors – hitting, shooting, tracking, and so forth, and often perpetuated against a woman. For example, instead of hitting a ball in a pong game, players bounce a icon of a woman back and forth. And instead of winning or losing a point, players hear a piece of the narrative in a voiceover. The story fragment is the reward for playing, but also the punishment –both the both the lure and the trap that advance the players forward to the inevitable end of the story – the killing of the woman.

I don’t think so much in terms of medium or media, since I think the computer has obliterated many of our traditional distinctions between them. Instead, I am concerned with concepts like time, space, and narrative, subjectivity, collectivity, and with producing different types of identifications within narratives.

My process in making Long Story Short has been quite different from that of a typical documentary filmmaker. I did not work with a producer, editor, or cinematographer. I used a laptop and webcam to shoot the video and I did not have a script. I developed my own language of montage, which includes an extremely intensive editing process, full of hundreds of jump cuts and loops. While Long Story Short shares themes with social-issue documentaries, it is not really a part of that genre. It is experimental in form and content and attempts to push the boundaries of documentary film, interrogate its forms, and offer an alternative approach. It takes on political questions and subjects both in terms of form and content, but rather than providing answers, it asks questions, and shows an aspect of our social lives that I would argue isn’t usually expressed in the social-issue documentaries we typically see on PBS, HBO, and Sundance.

NYFA: What strategies do you use as an artist to balance an ongoing project, such as Long Story Short, with other work and career goals?

NB: I don’t separate my work on Long Story Short from my art practice in general. I also teach – formerly at CalArts, now at Rutgers – and while I don’t have any original insights into how to best balance multiple simultaneous careers, I have found that each can stimulate and inform the other in sometimes really surprising and productive ways.

NYFA: Since the 1990s when you began using the internet as a medium for art making, digital technology and sociopolitical issues have been central themes in your practice. What do you think the terrain is like for artists interested in engaging in social issues today? How do you think the internet changed this landscape?

NB: In the years since I began working with the internet, artists, social critics, people who think about networks, have developed, by necessity, a much more sophisticated understanding of how networks work, and of just how invaluable they are for government and corporations, from the NSA to Google, in their ability to track, monetize, predict, categorize, and influence and control individual behavior. I think artists need to remain vigilant and up to date in reflecting on these conditions, and to intervene and propose and imagine alternatives.

NYFA: Based upon your extensive creative experience- West Coast and East Coast and making art and films and teaching and lecturing and engaging with communities (whew!)- what advice do you have for emerging media makers?

NB: Talk to each other. Share work, ideas, and invent and build new contexts for the production, distribution, and circulation of your work and ideas. Don’t rely solely on existing models. Invent new ones!

– Madeleine Cutrona, Fiscal Sponsorship Program Assistant

Learn more about Long Story Short by clicking here. Are you interested in using NYFA Fiscal Sponsorship to support your next great idea? Check out more details here.