The Business of Art: A Conversation with Will Insley

Comparing the present age to a half-century ago, it’s apparent how much more accessible the art world has become for young people. Graduate school programs groom young artists for immediate success in galleries eager to transition into what’s newest and hottest. In such a climate, the question of maintaining momentum as an artist becomes paramount. Will Insley is a New York-based artist who has been showing work since the mid-’60s. He has had solo exhibitions as the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the Walker Art Center, and Max Protech Gallery, and was included in Documenta 5. Insley also teaches at the School of Visual Arts in New York. NYFA Current editor Nick Stillman met Insley in his studio to discuss shifting art world paradigms and their effect on artists attempting to sustain successful careers.

Nick Stillman: Since you’re both a teacher and an active artist, you’re in a position of continuing with your own career as well as interacting with younger artists. In your opinion, has the art world changed from when you were beginning your career in the mid-’60s in terms of how it receives youth?

Will Insley: Yeah, it has changed. I had my first show in ’65 at Stable Gallery. Then the art world was much smaller. It was minute compared to what it is now. In many ways everybody knew everybody. There were fewer closed doors. For instance, I remember at Leo Castelli’s gallery you could just walk in and he’d be sitting there in the office and would say hi when you walked in. You can’t do that anymore. The difficulty in answering the question is that at that point I was a young artist so I saw through the eyes of a young artist. Now I see it through both the eyes of a young artist and through the eyes of a teacher who works with young artists. When I first showed I was 35, so I wasn’t as young as some.

NS: But that’s still a very young artist.

WI: Yeah, sure. Nowadays kids often start out showing when they’re 25.

NS: As someone who has observed that shift, do you think it’s a problem that artists now routinely show work when they’re so young?

WI: I don’t know how many people are really ready to make that leap when they’re 25. When I was 25 I didn’t know anything. I came to New York to be an artist, but I didn’t know quite what that meant. I went to graduate school as an architecture student for four years and after my jury I walked out the door and said to myself that whatever I was looking for there I didn’t find it. So eventually I decided I didn’t want to pursue a career as a professional architect and that I wanted the freedom of the arts. Still, I didn’t know what it meant to be an artist when I came to New York. The time between when I came to New York and had my first show was eight years. So I went through a good and sometimes very painful eight years—because I was very poor—but I had the time to work a lot of things out for myself. So I went through the growing pains of failure in the sense that I would try this or that and know it wasn’t working and it was very healthy to learn on the job. Which is opposed to nowadays when so many people go to graduate school, where you have the helping hand of your teachers. I didn’t have that, and you really learn a lot when you’re totally responsible on your own. When I was a young artist, very few people went to art school and thought that would be their key.

NS: Do your students think it will be their key?

WI: Oh, yeah. And I’m not completely saying people back then didn’t. The proliferation of art schools is actually very good for my generation because it has opened all these teaching jobs.

NS: Which is something I want to ask you about. What are the benefits of teaching as a career option for artists?

WI: There are many benefits! Particularly at a school like SVA because there are so many other artists on the faculty. Students have a choice now of art schools all over the country—it’s a big business.

NS: A market has really been created for graduate level studio art education.

WI: Yes, a market has been created. My generation came after the Abstract Expressionists. We didn’t go to graduate school. If I’d come to New York a little bit earlier I might have become a second-generation Abstract Expressionist (laughs). All you saw in New York in the late ’50s was Abstract Expressionism.

NS: That’s it, huh?

WI: Basically! There must have been some realist painters around, but only “with it” galleries were Abstract Expressionist-focused. But back to the point, I’d say artists now have a harder time getting teaching jobs than in my generation because there’s so much competition. Being able to teach was really a great boon to me, financially, and also because of the other people I was surrounded by.

NS: Can you identify what specific goals you had when you originally moved to New York?

WI: My goals were to survive, make a living. I always had part-time jobs.

NS: What types of jobs?

WI: My first one was with the Darling department stores. I worked every morning during the week and was a file clerk. Then the store ran into trouble and I needed to get a new job. So I asked myself where an artist might get a job and thought of the Metropolitan Museum. I wrote them a letter and quickly received a letter back saying there was an opening for a file clerk. So I was up there like a bat out of hell and I got the job. It was a great job that really made my life in several ways.

For one thing, one of my jobs was to process file cards—every object in the museum has a file card. So if things are in fragments, that’s numbered and explained, and that got me interested in fragments, which eventually became one of my basic motivations and has been all of these years. Also, I could just wander around the museum. This is an interesting story… I would always take the subway up the west side and walk through Central Park to work. One day I was walking across the park and a gentleman who was walking the same route introduced himself and it was Robert Hale, who was a curator in American art at the Met. He asked me to show him his slides. So the next day (laughs), of course, I went to his office and he looked at my slides and said he was the curator of dead Americans but that Henry Geldzahler was the curator of live Americans. I went down the hall and knocked at his door and explained that Robert Hale sent me to see him. He looked at my slides and asked, “Do you have a gallery?” I said I didn’t and he asked if I would like one. I said yes and said, “I’ll get you a gallery.” And he did. He brought dealers to my studio. He really changed my life.

I mean, that was luck, fate, I don’t know. But it happened. Now, one way or another I would have gotten through, but this gave me a few bonus points. Things just started falling into my hand, so in many ways I was extremely lucky. But being the smaller world that it was, it was easier to get lucky. Now the art world is so much larger.

NS: We talked before the interview about the perception of the art world as obsessed with youth. You intimated that this might not be such a new thing.

WI: Part of it is just that there’s so much more youth out there to pick from, so there’s more competition. There are more galleries to get involved with, but many galleries seem to be involved with a small group of people depending on what’s “hot this season.” In my generation we determined that, not the galleries.

NS: It seems like the influence that galleries and collectors wield now is something that may have changed over the past four or five decades.

WI: It’s very different. When I was young, I met a lot of other artists and realized that others were thinking about things that I was thinking about, people I had never known before—Bob Smithson, Eva Hesse, Robert Ryman, Sol Lewitt. Anyway, I think we determined where the art world was going to go; not the galleries. Of course the galleries picked up on things fast.

NS: That’s their job.

WI: It is. You might say we instantaneously picked up on it.

NS: If we can agree that we’re seeing the work of very young artists in galleries right now more then ever before, has this created a type of competition between older and younger artists? Have you seen it become more difficult for older artists to receive exhibitions?

WI: I think it’s on a case-by-case basis. But clearly there’s a generation debate going on. I want to refer back to Willem de Kooning and his famous comment about Andy Warhol. De Kooning thought that Warhol had destroyed art. He hated Warhol. I don’t think he ever spoke to him, but Andy didn’t stand for what he stood for. Clearly, it was a generation thing. But as a teacher, I don’t feel threatened like de Kooning did when a young artist wasn’t an Abstract Expressionist. Well, de Kooning spent most of his time getting drunk with Jackson Pollock (laughs). But by teaching, I’m moving ahead every year, so this isn’t an issue for me.

NS: Do you feel pressure to “stay contemporary” in your work?

WI: I want to remain myself and pursue my own information, irrespective of what is hot, irrespective of what is au courant, irrespective of what is fashionable. I have no choice because I’m led by my inner self. You never give that up, because if you do, you’re really lost. If artists don’t remain themselves, they seem to usually burn out.

NS: How does an artist not burn out?

WI: It depends on the person, but you must have faith in yourself, which is totally separate from anything that the rest of the profession will or will not determine for you.

NS: I’d like to read a quote of yours back to you: “The viewer becomes more involved as the art becomes more of a puzzle,” a statement that seems to praise art that rewards patient viewing. Is the concept of patient viewing something that’s changed?

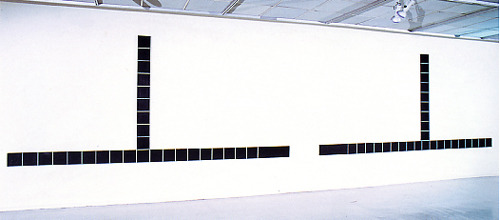

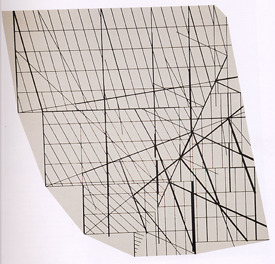

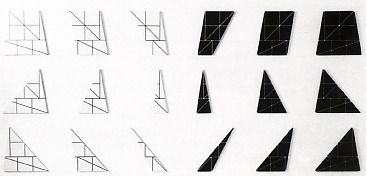

WI: I think it’s definitely changed. I think art should ask a question, not give an answer. That’s why fragments come into my work, so not all of the piece is there, begging the question: this is a fragment of what? Lots of people don’t have the intellectual curiosity to get involved in that question, but that’s what drives me. Now, there is no answer. If you’re looking for an answer, forget it. I think patience is virtually nonexistent now. This is more through general observation, but I do think a lot of people from my generation would agree with me. Observers now might think they have a lot of patience; it’s just that now patience is (claps hands) or (claps hands) and then on with the rush. People are always in such a damn hurry. Of course, the world has speeded up. Life has speeded up. But the heart still only beats so fast and there are still only 24 hours a day and you still have to go to bed at night and sleep.