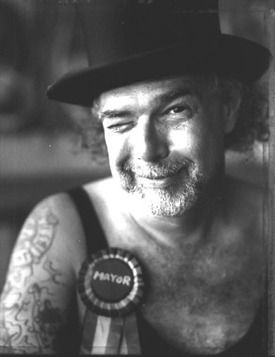

The Business of Art: A Conversation with Dick Zigun

(Photo: © Matthew Gerard)

It takes a certain élan to posit an insect-eating girl, a man in a straightjacket and a tassel-twirling stripper as embodiments of the “democratic golden age” of American cultural tradition. But that’s what Coney Island USA Artistic Director Dick Zigun has been doing since 1981, when he first established the Sideshow Museum, which was swiftly followed by the annual Mermaid Parade and Sideshows By The Seashore—the latter being one of the last remaining 10-in-1 sideshows in the US.

Zigun’s enterprising proved prescient; just a few years after he opened the Sideshow Museum a revived interest in turn-of-the-century-style “forgotten” entertainment resulted in an explosion of sideshow, vaudeville, and burlesque throughout the country. Coney Island USA’s stated mission is to “defend the honor of American popular art forms” through its exhibitions and performances. Just as the old freak shows were dying off or being banned from their usual location on state fair midways, young performers—some of them trained at Coney Island—began picking up the tricks of the trade and carrying them to rock clubs, theaters, and outdoor festivals. And there’s always been a charm about Coney Island itself, that enduring symbol of both romance and dereliction, which initially attracted Zigun and continues to draw audiences today. J. Dee Hill, author of Freaks & Fire: The Underground Reinvention of Circus, recently spoke with Zigun about growing up in P.T. Barnum’s hometown, New York City’s embrace of Coney Island USA, and the re-popularization of sideshow culture in American culture. Zigun is a 1985 NYFA Artists’ Fellowship winner in the category of Playwriting/Screenwriting.

J. Dee Hill: How did you arrive at Coney Island?

Dick Zigun: I grew up in Bridgeport, CT—P.T. Barnum’s hometown. Barnum was the mayor of Bridgeport; there are statues of Barnum, parks left by Barnum, the Barnum museum. Growing up in Bridgeport, you go to school and you not only learn about Abraham Lincoln and George Washington but Tom Thumb, too. You don’t realize until later that in the rest of America elephants aren’t just like vanilla ice cream and apple pie. So after finishing high school I got two fancy degrees in theater, finishing college at the Yale School of Drama. I went to New York, but instead of aspiring to Broadway, my childhood obsessions led me to the idea that Coney Island could be a staging ground for popular theater for the masses, an alternative to art “about” popular culture in a SoHo loft for 40 people. It’s more fun to be a down and dirty sideshow having to compete with all the other rides and attractions in Coney Island and to pull in an audience that didn’t wake up in the morning making a reservation to come to your show. They’re just walking by and you gotta grab ’em. That’s what’s fun about being here. What’s fun for the performers is that however art-smart and hip our cast is, it operates as a real sideshow, not as a commentary on sideshows.

Americans like American culture. A lot of what I had to do, what James Taylor [publisher of the Shocked and Amazed book series -ed] has been doing, is giving respectability, giving honor, back to blue-collar theatrical forms that prior to the 1980s were considered illegitimate. There have been questionable practices in the past with some sideshows, sure. But just to wholesale destroy or obliterate a culture is no better than the conquistadors destroying every book they found in Mexico because it wasn’t Christian. You don’t destroy your culture; you adapt it or change it if there’s something inappropriate. You advance it.

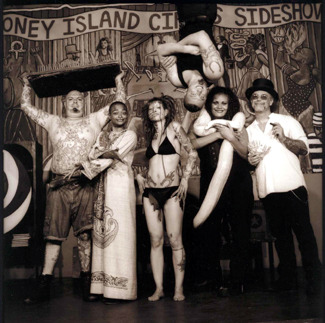

Coney Island Circus Sideshow cast (2004)

(Photo: © Aaron Beene)

JDH: Do you ever get complaints about your show? Horrified parents?

DZ: Some people think that the sideshow is too freaky, others think it’s too sexy. Some people think we push the edge. But that’s why we’re at Coney Island. It’s not a centrally managed amusement park, which means it’s a little more adult and not as standardized and homogenized and suburbanized as Disneyland. The audience for the sideshow is about 15% hipsters and the other 85%—the bread and butter of our audience—are the same people who are going to the beach, riding the rides. Our other programs, such as the burlesque shows and rock ’n roll shows, used to struggle quite a bit because you had that attitude of getting people from downtown Manhattan out to Brooklyn. But that’s changed dramatically since the mid-1980s. A lot of the arts community in New York is here in Brooklyn already, and you’re not struggling to get Manhattan people to go to the outer boroughs, you’re just getting people in Brooklyn to go to another part of Brooklyn. So suddenly the stuff that used to be hard to find an audience for is doing very well. We don’t pretend to be a sideshow frozen in time, a representation of how it was in the 1950s. We’re 21st century, we’re New York City. That’s what makes it real. The diversity makes it real. But it can be hip and self-aware at the same time.

JDH: You were doing burlesque here 20 years ago?

DZ: The new burlesque movement and the sideshow revival both got started with us at Coney Island. As far as I know the new burlesque was specifically started by Erica Peterson, who called herself Wild Girl and was doing “Wild Girl Go-Go-Rama” back in 1986. It was go-go stripping but not pure sexy; kind of a hybrid.

JDH: Why do you think these old forms such as sideshow and vaudeville seem so relevant now?

DZ: I think [sideshow is] something with the creativity of performance art but with a uniquely American flavor and a tremendous ability to please an audience with virtuoso skills. Unlike Stanislavsky’s acting, where audiences try to find themselves in the character, the sideshow movement is about a virtuosity that informs everything you do. So it’s not just about acting skills, it’s about being a sword swallower or hammering hails in your head or breathing fire.

When I went to school my teachers thought I was nuts. There certainly wasn’t any place, in any school in America where you could get a degree or even take a class in this stuff. It’s like American theatrical history began with Eugene O’Neill. To go from that to meeting a whole younger generation of people who go to the performance studies program at NYU and get degrees in sideshow and seeing books and journals and classes—it’s amazing how mainstream this kind of thing has become with sideshow entering rock videos and advertising on commercial TV. It’s just fully integrated, or re-integrated, back into American culture. It’s probably as influential as it was in the last century when there were 50 sideshows touring the country. When Michael Wilson first worked here, he—aside from being heavily tattooed—did a shocking act where he hammered a nail through his tongue at every performance. And it was no big deal because he had a pierced tongue, but that wasn’t common then. Now every suburban 16 year-old girl in America has a pierced tongue and tattoos. And it’s partially our bad influence. Really, it’s been astonishing to watch, just how influential it’s become and knowing how weird and unknown and isolated it was not that long ago.

Michael Wilson (1996)

Former Coney Island Circus Sideshow performer

(Photo: Carl Saytor)

JDH: What’s the future of Sideshows by the Seashore at Coney Island?

DZ: Real estate in Coney Island has taken off over the last few years, tripled in price. Half the property has changed hands. And I’ve got a big smile on my face because the New York City leadership has put money in the city budget for us to buy real estate so we can go from being renters to being owners. We’re deliberately expanding our board, expanding our staff. We’re doubling the size of our budget. There is a plan to institutionalize the programs, so that the things I and other people have set in motion will outlive us. It’s satisfying to know that despite the neighborhood changes and the demographic changes we will really create something here to perpetuate certain art forms. New York is the cultural capital of the world, and if you are going to seriously make a national statement about American popular culture, Coney Island oddly enough turned out to be a smart place to base it. It works here, it belongs here, the history is here.

J. Dee Hill is a journalist and author of Freaks & Fire: The Underground Reinvention of Circus, published by Soft Skull Press. To contact her, email: [email protected].

For more information on Dick Zigun and Coney Island USA, which produces Sideshows By The Seashore and other events, visit:

www.coneyisland.com