The Business of Art: A Conversation with Kyung Jeon

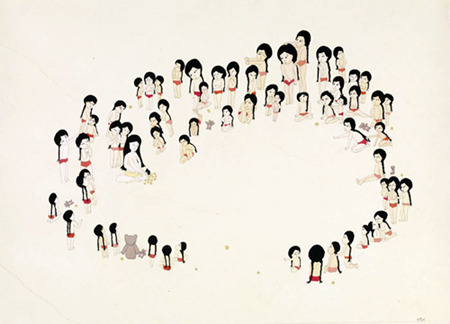

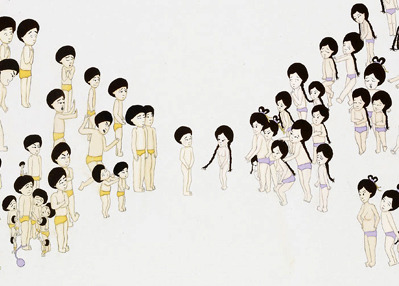

Like the technicolor allure of poisonous frogs or the dazzling yet deadly pufferfish, Kyung Jeon’s paintings act as decoys — her soft, pastel colors; fields of flowers; and flitting fairy-children initially cloud the sinister grotesquerie of her perspectiveless panoramas.

Jeon’s disfigured figures are antagonized and accosted in ways that allude to Hieronymus Bosch’s depictions of hell—bodies are flayed and abducted, beaten and brutalized. In her large-scale painting Overload, a trio of boys are hacked to pieces by axe-wielding sprites while a splayed-out teddy bear is tied down as if forced to witness a murder. Raised in a Christian household, punishment and retribution are familiar themes for Jeon.

Like Goya’s later works—the “Black Paintings” of crazed pilgrims and witches that the Spanish artist painted while nearly blind—the Korean-American artist’s paintings carry a dark undercurrent. Even paintings as seemingly benign as Thumb Suckingcharts dark territory. As the title suggests, a group of girls half-hidden in a cluster of flowers stuff thumbs and other digits into their mouths, loading reflex and habit with sexual overtones. P.S.1 Curatorial Assistant Christopher Y. Lew caught up with Jeon in her TriBeCa studio while she was preparing for her upcoming solo show at The Proposition in New York.

Christopher Y. Lew: Storytelling is implied in your paintings. What are your interests in narrative?

Kyung Jeon: I started off creating drawings and paintings that really didn’t show much narrative at all. They were just figures in empty space, just moments, and I wanted to go deeper into that so I created these larger pieces with more figures and they became more narrative. The figures started interacting with each other more and, using my weird imagination, I made the story really dream-like, partially by exaggerating and distorting bodies. But I don’t necessarily think of any piece as a continuous narrative or story. I think that they’re each showing different moments, different interactions.

CL: You mentioned drawing on your imagination and how you’ve incorporated elongated or somehow distorted bodies into your paintings. Fairies and stretched-out breasts appear a lot. Do these symbols hold specific meanings?

KJ: The fairies get to act however they want. Things that I could never think of doing are things the fairies get to do. I use them in a humorous way. I like that they get to do these naughty, uninhibited things. Their absurd violence is kind of funny.

The elongated breasts originally appeared in my work in the form of breasts spilling out milk and from the thought of milk as the essence of life that feeds the body or mind. It sort of evolved into these stretched out things, becoming something burdensome. These beautiful things are now dragging on the ground.

CL: Looking at On Marriage and On Motherhood, you have a range of figures that are physically expressing their thoughts about the relationships referenced in these titles. Yet the characters feel like archetypes instead of specific individuals. How did you negotiate using general figures for these particular issues?

KJ: On Marriage is based on people close to me, specifically my brother, who is the first in the family to marry. On Motherhood is based on my closest friend, who just had a baby. It was interesting how everybody reacted so differently to the idea of my friend having a baby and to my brother getting married. The characters in my paintings are sometimes very generalized because a lot of people can relate to their situations. But some of them are very specific people.

CL: Your imagery blends cuteness and violence. Is that a comment on parenting or children?

KJ: No, I don’t think my work is ever about children. I use children as a way for people to approach these pieces in an easy way. People can come up and think, “Oh this is cute. There are a lot of little kids.” They think it’s really sweet, but realize it’s actually not. And if I’ve drawn them in that much then they can realize the really weird things going on. Kids and pretty colors can pull people in. I like that moment when someone thinks a painting is a sweet piece, and then realizes it’s not. That moment is crucial in my work. I like to see people look at my paintings and smile, then approach it and frown a little.

CL: Are there artists or works you keep in mind when you’re painting?

KJ: I like this Korean traditional painter a lot, Lee So-Ji. He uses a lot of Korean characters, villages, and mountainous landscapes. I like to look at his work for composition and to get ideas because I’ve been using landscape a lot more. And I go to Google if I’m researching things like underwater imagery. I do image searches and flow through everything that comes up.

Sometimes I get inspired by specific pieces. Joust Fight was after Goya’s bullfighting drawings. I thought the composition was interesting so I drew from that. But I played with it, switching from a bullfight to a joust and the boys became horses with several arms. They first had two arms, but it was too boring. They needed more to make them move quickly.

CL: How did you decide to work with rice paper?

KJ: Several years ago I asked my father to bring me some rice paper from Korea. At the time I was working directly on canvas. This was a way to incorporate my Korean identity because at the time I wasn’t using any Korean imagery or materials at all. My paintings then were just goopy abstractions.

I was experimenting with the rice paper on vinyl, on wood, and on other stuff. Then I came up with the technique of putting it directly onto canvases that had been primed and gessoed four times. It holds the rice paper and creates rips and textures, bubbles and stuff, which I really like. And I like how watercolor looks great against this natural yellow. Even acrylic and gouache looks lovely against the paper. So do big washes of color that become so uneven because of inevitable rips and tears to the paper.

CL: You’ve really created your own method of working with a material that carries the weight of Korean cultural history with it.

KJ: I’ve tried to paint directly on the rice paper but everything just ripped and fell apart. I needed a way to make it hold paint. Traditionally, sumi ink is applied to rice paper. I was using heavy acrylics and it was just bleeding through. My way isn’t a traditional way of using rice paper, but this has been working for me for years now. People think it’s heavy paper and they realize it’s not. It’s something else, a thin paper over something, and I like that.

CL: You’ve begun to show your work in Korea.

KJ: Yes, first I showed at the Seoul Arts Center and a curator saw that show and invited me to the Art Spectrum 2006 show at the Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art. Someone at Kukje Gallery saw that show and now I will be in a three-person show at the gallery in February. I’m really excited about that one.

I honestly didn’t know how Koreans would react to my work. Korean-Americans seem to respond to it really well since they can relate to it. But I honestly did not know how Koreans would take it. I thought they were more conservative and so I was a little nervous.

CL: And what was the response?

KJ: Since the exhibitions were at museums nobody bought anything so I didn’t know from that. Teenagers would come up to me and say, “Wow, how did you get those ideas?” and “Your paintings are so cute.” The language barrier made it hard, but the kids responded to it and adults are responding now, too. By working with Kukje some Koreans are now buying the work, which is nice.

CL: What is the project you’re working on with John Zorn?

KJ: It’s a book. I wrote a children’s fairy tale. Well, it’s written in the style of a children’s book, but it’s not really meant for children. It’s about this character Mi Ja. The idea came from Plato’s allegory of the cave from The Republic. That story has always been with me. I love the idea of realizing something as it really is instead of what it appears to be… that journey of understanding. So Mi Ja goes through thisWizard of Oz-style adventure. She meets characters, discovers things, and falls in love.

John is going to write the music for the book. My first thoughts of the book were based on Korean folktale books I grew up on. They were always accompanied by cassette tapes where the story was told in English on one side and in Korean on the other side. We would listen to the Korean side but not really understand anything. It was kind of like music. When John proposed to do the music for the book I was honored and thrilled. He’s going to do the music that can you listen along with as you’re reading the book.

CL: And you’ll do the illustrations as well?

KJ: Yes, I have done the illustrations. The story and illustrations are finished and we’re waiting on the designer and music and everything. It should be coming out next year. I’m excited. It’s my first collaboration and to do it with John is pretty amazing.

Kyung Jeon’s solo show The Impulse Garden is on view at The Proposition, New York, from September 16-October 28.